大国重拳

习近平对其国家互联网巨头的制裁可能弄巧成拙

在过去二十年里中国的所有成就中,最令人印象深刻的就是其科技产业的崛起。阿里巴巴运营着亚马逊两倍规模的电子商务活动。腾讯运营着世界上最流行的,有着12亿用户量的超级app。中国的技术革命也为其长期国内经济发展转型提供了更多愿景,这些技术不只用在制造业,进而跨越到了更多新的领域,如数字医疗和人工智能(AI)。推动中国的繁荣的同时,令人眼花缭乱的科技产业也可能成为挑战美国霸权的基础。

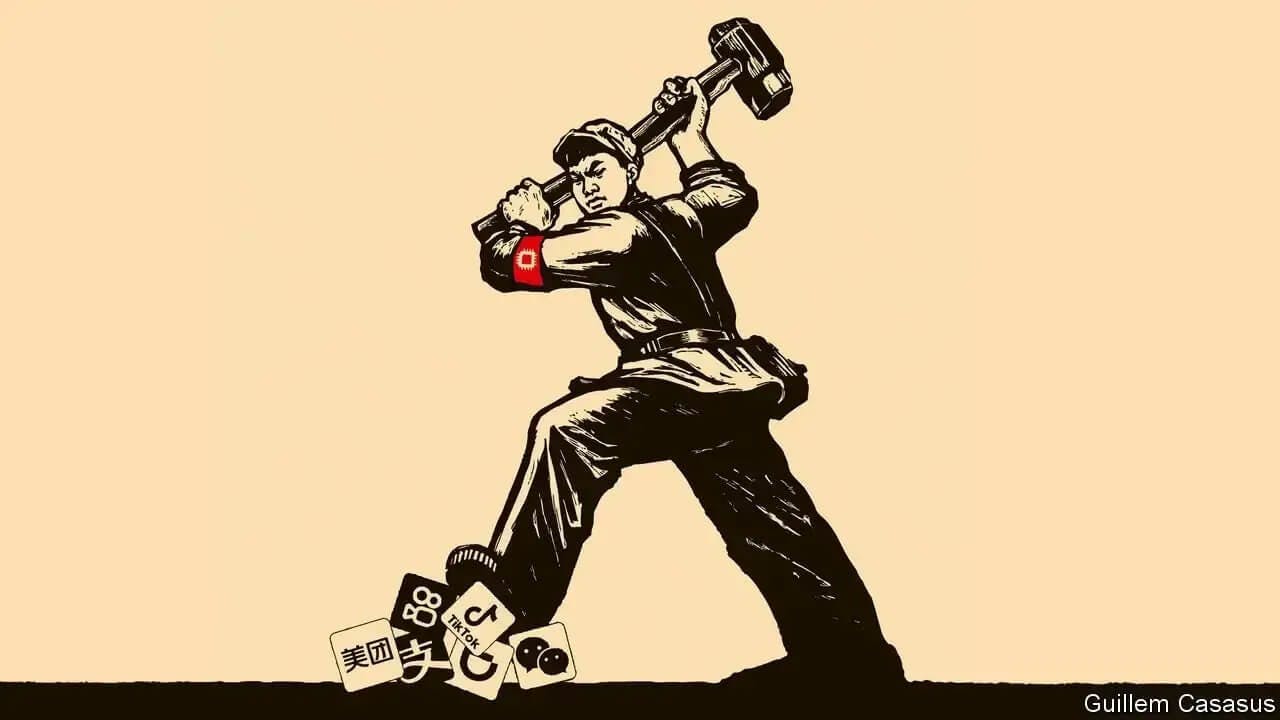

这也是为什么习近平主席对其4万亿美元科技产业的制裁如此令人震惊。从恶意垄断到数据滥用,针对几十家公司的被指控涉及一系列让人头晕眼花的违规行为,目前已经实施50多起管制措施。政府禁令和罚款的威胁已经拖累了股价,致使投资者已经损失了大约1万亿美元。

习近平先生的直接目的可能是想敲打一下富豪们,同时让监管机构对无序的数字市场掌握更多控制权。但是在我们看来,共产党更深层次的野心在于按照其构想来重新定义整个行业。中国的独裁者希望这能强化其国家科技优势,同时促进竞争并惠及消费者。

地缘政治可能也让他们如鲠在喉。获取以美国技术制造的部件的受限使中国认为它需要在半导体等核心领域更加自主。如果对类似社交媒体、游戏公司的打击能将优秀的工程师和程序员引导向这些领域,是可能有助于发展这些“硬科技”。然而制裁也是一场豪赌,也可能结果给产业和经济增长造成长期损害。

二十年前,中国连技术突破的门槛都摸不到。阿里巴巴这样的先驱在硅谷眼里也不过是山寨者,直到他们在电子商务和数字支付上反客为主。如今有73个中国数字公司估值超过100亿美元。其中大多数有西方的投资人或者国外教育背景的高管。充满活力的风险投资生态系统里也不断涌现出新的明星。在中国的160家“独角兽公司”(估值超过10亿美元的创业公司)中,有一半是在人工智能,大数据和机器人等领域。

与普京在世纪初和俄罗斯寡头的斗争不同,中国的制裁不是自己人获利不均的内斗。事实上,这反映了一直困扰西方官僚和政客的难题:数字市场趋于垄断的性质让科技公司得以囤积数据,以此侵压供应商,剥削工人并且威胁公共道德。

早该管管了。中国改革开放时,党牢牢掌握了金融、通信和能源的命脉,而对科技行业信马由缰。他们的数字先驱者们利用这种几乎缺位的监管,野蛮生长。提供出行服务的滴滴,用户数量比美国人口还多。

然而,大型数字平台也利用他们的自由来践踏小公司。他们禁止商家在其他平台销售。他们剥夺了送餐员和其他临时工的基本福利。党想要终结这种不当行为。这是许多投资者支持的壮举。

问题是怎么做?中国即将成为一个政策实验室,验证一个蛮不讲理的国家如何与世界上最大的公司争夺21世纪的新基础设施的控制权。有些像土地和劳动力一样,被该政府称作“生产要素”的数据,可能会转为公有制。国家可能会强制要求跨平台的可操作性(比如说,微信不能再屏蔽竞争对手)。利用成瘾机制的算法可能会受到更严格的监管。所有这些可能会损害利润,但可能使市场更好地运作。

但是别搞错了,这种对中国的放肆的科技公司的制裁同时也是党的权力不受约束的表现。过去它的工作中心往往落到既得利益者头上,包括腐败的官僚,而且往往受制于争取境外投资和创造就业的需要。现在党有恃无恐,目不暇接地出台新规定并且饶有兴致地强制执行。中国在监管上的不成熟暴露无遗。不过五十来个人组成了它的反垄断机构主体,但是他们动动笔杆子就能摧毁一个个商业模式。没有正规程序,公司们只能苦笑着接受。

中国的领导人们成功地浪费了几十年用来学习西方自由经济范例的时间。他们可能认为他们对科技行业的钳制是在完善其国家资本主义政策——一个为了维护国家稳定和确保党的执政地位的集繁荣与控制于一身的蓝图。事实上,随着中国人口开始下降,党希望从国家方向来提高生产力,包括工厂自动化和城市巨型集群化。

然而对重塑中国科技产业的尝试很容易行差踏错。这可能会引起海外的疑虑,阻碍中国在21世纪向全世界出售服务和制定行业国际标准的雄心壮志,就像美国20世纪那样。对增长的任何拖累都会远远超出中国的承受范围。

一个更大的风险是,制裁会钝化在中国的企业家精神。随着经济从制造业向服务业转移,在复杂的资本市场背景下,自发的风险承担会越来越重要。中国的几个领头的互联网大佬已经从他们的公司和公共生活中抽身。后来者们效仿他们前会三思,尤其是因为制裁让成本大大增加。

创业放缓

目前中国最大的科技公司每美元的销售额相对美国公司有平均26%的折扣率。 初创企业,例如通过地图应用从滴滴手中抢走打车业务的小公司们,一直在蚕食政府的主要打击目标。 他们非但没有因为制裁而摩拳擦掌,反而感受到了风险。 有创造力的破坏是经济发展的应有之义。 中国的专制领导人们证明了他们可以进行破坏。 而这次科技动乱能否带来创造力则前途未卜。

译后

以后可能会翻译一些“有意思”的经济学人的“Leaders”栏的封面文。 因为不是有偿翻译,所以选择翻哪些期,跳过哪些期的权力我应该可以保留,是吧。也就是我说的“有意思”,比如说这一篇。

这篇文章基本上还算是中立,可是对共产党的态度非常鲜明。 文章的核心思想,用知乎典型的阴阳怪气键政黑话来说就是,“早该管管了,但是谁来管管共产党我暂且蒙在古里”。

我不对文章本身作任何更多评价,只简单说一下我对这个话题的一点点想法。 算力就是第三次工业革命的生产力,过去曾经是蒸汽,曾经是电;数据就是能源,过去曾经是煤矿,曾经是石油,这不需要谁来指称,更无需谁揶揄“生产要素”这个说法。 我一直误解的是,我曾经认为只有我们的体制需要政体出于自保的机制来制衡资本的过度增长。 因为显然的,如果我们的资本市场是中国特色的,那么我们的反垄断机制也肯定得是中国特色的,直白点就是如果资本的规模威胁到了共产党的领导了就是到了需要反垄断的时候。 毕竟中国特色的本质就是中国共产党的领导,我不是来上党课的,就不展开了。总之在这个点上,这篇文章说得也没有差太远。

我看这篇文章最大的收获是,原来正宗的资本主义国家其实现在也很焦虑,其实他们的反垄断机制也正面临新的挑战。 而我们这样的强硬的霹雳手段,也正是标榜自由的市场想做而做不到的。 自由市场的反垄断机制本质上来说是玩家们在自觉遵守游戏规则,现在自认为遵守游戏规则的玩家们发现游戏开始发生变化了。 这个问题之所以棘手,最大的难点其实文章里面也说到了,digital markets tend towards monopolies,数据只有统计学意义,那么必然是排他的。 你可以把能源公司拆分,即使他们以后还是合作开发油气,多种不同矿产也不能相互反应产生累进的价值,但在数据这里这些规律都不适用。 如果说资本过去可以比作癌细胞,那么不同的癌细胞可以占领不同的器官。 但是数据产业的性质更像艾滋病毒,通过逆转录攻击防御系统完全占领宿主并形成破坏力,而且往往就是由癌细胞来实现真正的杀伤,正如科技公司通过大数据来钻空子,实现资本的扩张,巧的是后者刚才被我比作癌细胞。 甚至,我们可以了解到,病毒的生物学本质都确实就是一段数据。

而所谓强硬的手段,其实在我们这也不是很轻易就能做到的。我相信如果不是一直以来的整风运动,现在开展的很多工作恐怕都很难展开。 你可以说这是某个人的远见,或者也可以说,这是党在特定历史时期为了实现自保的必然举措。

我不太喜欢经济学人的最大一点是,就像上面这样,大话谁都会说,但是我们真正该关心的是每个人。 如果党能像过去的几十年一样改善中国人的生活,那么一切都无所谓对错,一切都是值得的。 而党的工作重点显然要比经济学人这帮大头编辑要实在的多,明确我们的主要矛盾现在是分配问题,而不是居高临下地评估这个造富工厂是不是要减产了。

原文

原文Xi Jinping's assault on tech will change China's trajectory,以题为 China’s attack on tech 于8月14日刊载在《经济学人》。

China's attack on tech

Xi Jinping's assault on his country's tech titans is likely to prove self-defeating

Of all china's achievements in the past two decades, one of the most impressive is the rise of its technology industry. Alibaba hosts twice as much e-commerce activity as Amazon does. Tencent runs the world's most popular super-app, with 1.2bn users. China's tech revolution has also helped transform its long-run economic prospects at home, by allowing it to leap beyond manufacturing into new fields such as digital health care and artificial intelligence (ai). As well as propelling China's prosperity, a dazzling tech industry could also be the foundation for a challenge to American supremacy.

That is why President Xi Jinping's assault on his country's $4trn tech industry is so startling. There have been over 50 regulatory actions against scores of firms for a dizzying array of alleged offences, from antitrust abuses to data violations. The threat of government bans and fines has weighed on share prices, costing investors around $1trn.

Mr Xi's immediate goal may be to humble tycoons and give regulators more sway over unruly digital markets. But as we explain, the Communist Party's deeper ambition is to redesign the industry according to its blueprint. China's autocrats hope this will sharpen their country's technological edge while boosting competition and benefiting consumers.

Geopolitics may be spurring them on, too. Restrictions on access to components made with American technology have persuaded China that it needs to be more self-reliant in critical areas like semiconductors. Such “hard tech” may benefit if the crackdown on social media, gaming firms and the like steers talented engineers and programmers its way. However the assault is also a giant gamble that may end up doing long-term damage to enterprise and economic growth.

Twenty years ago China hardly seemed on the threshold of a technological miracle. Silicon Valley dismissed pioneers such as Alibaba as copycats, until they leapt ahead of it in e-commerce and digital payments. Today 73 Chinese digital firms are worth over $10bn. Most have Western investors and foreign-educated executives. A dynamic venture-capital ecosystem keeps churning out new stars. Of China's 160 “unicorns” (startups worth over $1bn), half are in fields such as ai, big data and robotics.

In contrast to Vladimir Putin's war on Russia's oligarchs in the 2000s, China's crackdown is not about insiders fighting over the spoils. Indeed, it echoes concerns that motivate regulators and politicians in the West: that digital markets tend towards monopolies and that tech firms hoard data, abuse suppliers, exploit workers and undermine public morality.

Stronger policing was overdue. When China opened up, the party kept a stifling grip on finance, telecoms and energy but allowed tech to let rip. Its digital pioneers used this near absence of regulation to grow astonishingly fast. Didi, which provides transport, has more users than America has people.

However, the big digital platforms also exploited their freedom to trample smaller firms. They stop merchants from selling on more than one platform. They deny food-delivery drivers and other gig workers basic benefits. The party wants to put an end to such misconduct. It is an ambition that many investors support.

The question is how? China is about to become a policy laboratory in which an unaccountable state wrestles with the world's biggest firms for control of the 21st century's essential infrastructure. Some data, which the government says is a “factor of production”, like land or labour, may pass into public ownership. The state may enforce interoperability between platforms (so that, say, WeChat cannot continue to block rivals). Addictive algorithms may be more rigorously policed. All this would hurt profits, but might make markets work better.

But make no mistake, the crackdown on China's unruly tech is also a demonstration of the party's untrammelled power. In the past its priorities often fell victim to vested interests, including corrupt insiders, and it was constrained by its need to court foreign capital and create employment. Now the party feels emboldened, issuing new rules at a furious pace and enforcing them with fresh zeal. China's regulatory immaturity is on full display. Just 50 or so people staff its main anti-monopoly agency but they can destroy business models at the stroke of a pen. Denied due process, companies must grin and bear it.

China's leaders have spent decades successfully defying Western lectures on liberal economics. They may see their clampdown on the technology industry as a refinement of their policy of state capitalism—a blueprint for combining prosperity and control in order to keep China stable and the party in power. Indeed, as China's population starts to decline, the party wants to raise productivity through state direction, including by automating factories and forming urban mega-clusters.

Yet the attempt to reshape Chinese tech could easily go wrong. It is likely to raise suspicion abroad, hampering the country's ambitions to sell services and set global tech standards worldwide in the 21st century, as America did in the 20th. Any drag on growth would be felt far beyond China's borders.

A bigger risk is that the crackdown will dull the entrepreneurial spirit within China. As the economy shifts from making things towards services, spontaneous risk-taking, backed by sophisticated capital markets, will become more important. Several of China's leading tech tycoons have pulled back from their companies and public life. Wannabes will think twice before trying to emulate them, not least because the crackdown has jacked up the cost of capital.

Startup slowdown

China's biggest tech firms now trade at an average discount of 26% per dollar of sales relative to American firms. Startups, such as the minnows taking ride-hailing business from Didi with mapping apps, have been nibbling at the government's main targets. Far from being emboldened by the crackdown, they are likely to feel exposed. Economic development is largely about creative destruction. China's autocratic leaders have shown that they can manage the destruction. Whether this tech tumult will also foster creativity remains much in doubt.

The 1st of 1 post in collection The Economist